SANTA BARBARA IS MY HAPPY PLACE, A PLACE TO lose myself on the beach boardwalk, breathing briny sea air thick with the caw of gulls. This time I drove down to explore the Funk Zone: a 10-square-block area of old warehouses, manufacturing and industrial plants. The once marshy streets, blue-collar all the way with rent cheap enough to attract those who worked with their hands: surfboard shapers, boat-makers, candle-dippers, auto mechanics, and more.

I booked the Franciscan Inn & Suites (www. franciscaninn.com) after hearing one of its wings had been a 1920s Spanish-style house, part of a beachside ranch. Rooms 101-103 are the original ranch house; rooms 104-107, former stables.

The property was purchased in the 1930s and converted into a small motel,” said Debbie Neers, General Manager. “My mother remembered it from her childhood.”

In the mid-1970s, Debbie and her parents drove up to see it one last time before it sold. “We found decaying little cottages. My mom actually fell through the floor in one of the units.”

In 1976, her parents bought the motel, rebuilt it from the ground up, and later purchased two neighboring motels. Combined, today’s Franciscan Inn has 53 rooms.

From there, it’s a brief walk to the Visitor Center, built with sandstone blocks in 1911. The building was later moved to its current spot, catty-corner to Stearns Wharf (circa 1872), the oldest working wooden wharf on the West Coast. The wharf helped solidify the harbor’s packing warehouse district, which is today’s Funk Zone.

I’d hoped the center would have a map showing which historic buildings had housed which operations and list the years. No such luck. “How did the Funk Zone get its name?” I asked. The staff looked puzzled. “I don’t know.”

The more questions I asked the more frustrated I became at contradictory answers. A friend told me about John Ummel, a former high school social studies teacher who leads free walking tours of the neighborhood (www.freewalkingtoursb.com).

I met John in Palm Plaza on State Street, spotting his signature red ball cap. “In the late 1990s, after being neglected for decades, the Funk Zone began to attract attention from developers,” he told me. “Around that time, the city was getting anonymous complaints about building and zoning code violations.

“As the story goes, a couple of city officials were strolling through the district. One is said to have commented, ‘Wow this place is funky,’ and the name stuck.” That works for me.

A de facto ambassador, John carries an oversized notebook with hand-chosen photos of original buildings, such as Hotel California, destroyed in the 1925 earthquake a mere 11 days after it opened.

“Santa Barbara became the first city in the country to mandate a specific type of architecture when rebuilding.” He pointed to ornate designs in a photo. “Spanish colonial.”

Nearby, the old Bekins Van and Storage building (circa 1914) survived the earthquake. “The walls are reinforced concrete,” he said. “During its heyday, 400 trunks arrived each day to be stored.”

During the tour he shared lively anecdotes while we crisscrossed railroad tracks, explored dead-ends, and skirted chain-link fences. A grain silo (circa 1949) connects to the Weber Baking Co. building (circa 1930s), home of the first loaf of sliced bread. “Hence the saying, ‘the best thing since sliced bread,’ John said over a train whistle. “ Wonder Bread makes the same claim.”

I’d done a bit of research myself, reading about land surveyor Salisbury Haley who plotted the street grid in the mid- 1800s. He’s legendary for confusing block measurements and misaligning streets, which spawned odd doglegs at certain intersections.

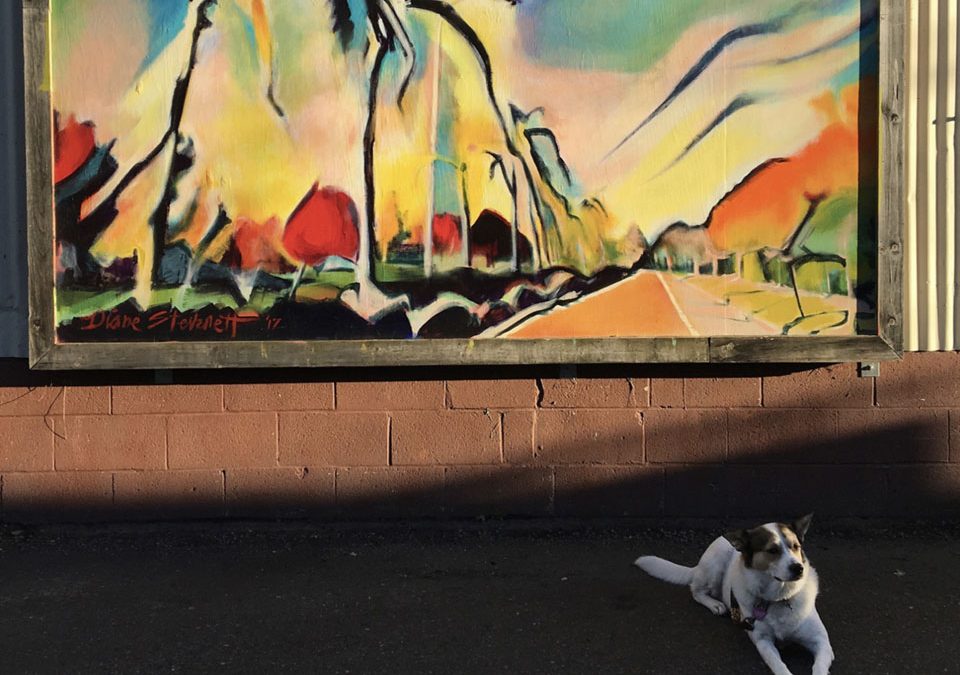

John explained the public art displays. “They’re typically large formats on the sides of buildings—started in 2009 when a landlord gave a tenant permission to replace broken windows with art panels.”

Murals, collage, and poster art appeared everywhere: On curbs, telephone poles, even a Quonset hut set down after World War II. On the intersection of Yanonoli and Gray Streets, an artist stood high atop a mechanical lift, a can of black paint in one hand, and a wide brush in the other. He’d been working from the sidewalk up—about to finish a conceptual tiger.

Across the street, bi-fold, roll-up garage doors had been painted by art students from Santa Barbara High School. The doors were raised, creating a Renaissance-type ceiling over the sidewalk.

John paused by a pair of Ruth Ellen Hoag’s murals. “They were inspired by local historical figures and places. It’s the old Coast Wholesale Grocery Co. building (circa 1918).

I scanned faces, recognizing Jonathan Winters and Jimmy Buffet. Hoag’s website (www.ruthellenhoag. com) has templates that match names to figures. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have placed foremost surfboard shaper Renny Yater. Two of his boards appeared in Apocalypse Now, Francis Ford Coppola’s outré film set during the Vietnam War.

Contemporary murals line the side of a half concrete-block, half corrugated building once marred by graffiti, in an alley off Anacapa Street. I was taken by a large framed piece showing six red-tinged photos of a young Muhammad Ali.

An old-time telephone booth stands alone at the edge of a parking lot. Painted Day-Glo red, it’s labeled Book Exchange. Inside, only a few battered paperbacks.

Street-side, Corks and Crown wine-tasting room and two attached buildings were once psychiatric barracks and temporary quarters for returning World War II veterans. That day, the patio was four deep waiting to sample wine.

Tune in next month for Part II of Santa Barbara’s Funk Zone.