“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

—Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution

Persistence. In a word, it’s what led to the ratification of the simply worded 19th Amendment to the Constitution on August 18, 1920. While many states recognized voting privileges for both men and women, now all women were guaranteed the right to vote. Period.

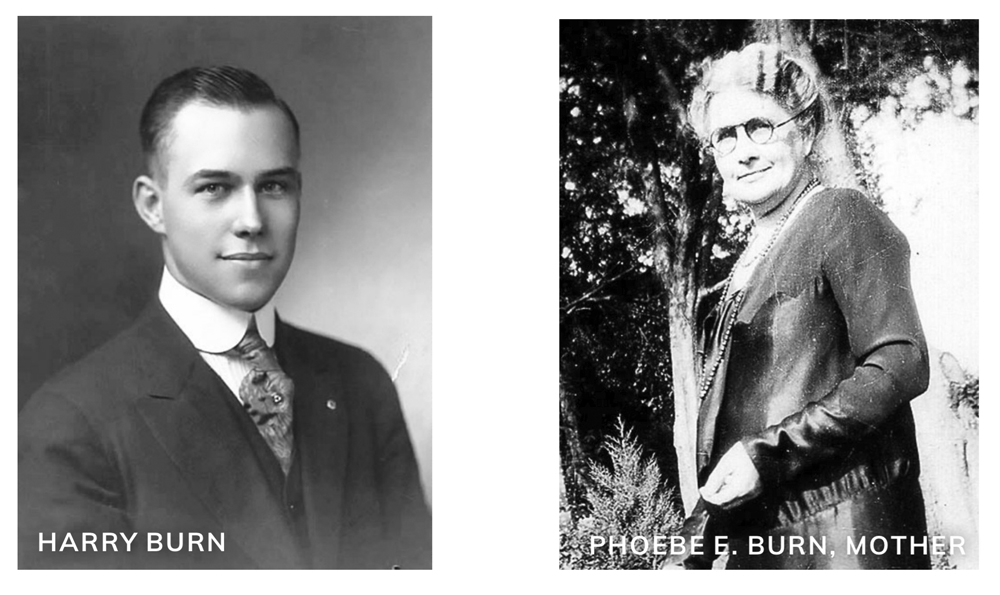

Tennessee’s dramatic endorsement sealed the ratification. It seems 24-year-old Senator Harry T. Burns’ mother sent her son a letter. Known by all as Miss Febb, she wrote: “Hurrah, and vote for suffrage!” Supporting the efforts of Carrie Chapman Catt who would go on to found the League of Women Voters, Miss Febb ended with “be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt.” He was, and all women could now vote. California voters agreed and became the 18th state of the 36 needed for ratification the previous November.

The amendment’s constitutional heritage started with the 13th Amendment (abolishment of slavery), the 14th (equal rights), and the granting of the franchise to “all black men” in the 15th. While none included women specifically, the glacial efforts to first change collective attitudes and then laws were as old as the Nation. Interestingly, California did not ratify any of the three until after they were enacted by a majority of the states.

While a glorious headline to the continuing efforts to provide legal gender equality in America, it certainly wasn’t the last stop on the train of justice. Nonetheless, the date is among the crown jewels of democracy.

It becomes an even more spectacular achievement when cast against the decades of lone and united voices—by both women and men—in communities across America underscoring the necessity, not the option, of allowing all citizens to come to the ballot box and in that moment at least join in united equality with all other citizen voters.

The amendment’s constitutional heritage started with the 13th Amendment (abolishment of slavery), the 14th (equal rights), and the granting of the franchise to “all black men” in the 15th. While none included women specifically, the glacial efforts to first change collective attitudes and then laws were as old as the Nation. Interestingly, California did not ratify any of the three until after they were enacted by a majority of the states.

While a glorious headline to the continuing efforts to provide legal gender equality in America, it certainly wasn’t the last stop on the train of justice. Nonetheless, the date is among the crown jewels of democracy.

It becomes an even more spectacular achievement when cast against the decades of lone and united voices—by both women and men—in communities across America underscoring the necessity, not the option, of allowing all citizens to come to the ballot box and in that moment at least join in united equality with all other citizen voters.

Nor was the vote solely a right to hold elective office. Prominent advocacy emphasized the moral imperatives. “It is for the Common Good of All” pleaded the activists.

As a state, California replicated much of the nation by cheering progress, chastising dissenters, and climbing the summit at whose top awaited the reward of national law and not simply state directives. Yet, the battle needed to be fought state by state.

Decades of advocacy, failures, and successes large and small emboldened the cause. “Failure is impossible” was the mission statement. Many Californians dearly wanted to join the elite group of states led by Wyoming in 1890, then Colorado three years later in extending the franchise to resident women. All it took was to convince a majority of voter—all male—to agree with them.

The story continues.

In the small county and even smaller county seat with the same name, San Luis Obispo suffragists were eager to have their voices added to the grander scale marches by suffragettes in their blue, gold, and green regalia. Distractors were expected as the Sacramento Bee reported in 1895. It seems those opposed to the idea used female association with bloomers and pantaloons to ridicule the advocates as “pantaloonatics.”

Undeterred by any name-calling, locally, the Political Equality Club of about 20 ladies (and three men) “became a very lively aggressive organization” in May 1896 preparing for the pivotal November state election. Composed of many leading members of the community, any opponents were characterized by the press as “Salurians” or rock brains. The editor praised the gathering which showed “plainly that the women of this city—the wives and mothers—know what they want, and propose to obtain it if open argument and honest effort can obtain it.”

Included among the leaders were Francis Margaret Milne, soon to be the city librarian (see April 2019 issue) and Miss Kate Cox who preferred being characterized as a “capitalist.” She will become the oldest woman in the county to register to vote once approval was secured in the state. The ladies were in a “feverish state of excitement” and men were advised to remain silent.

Adding their voices to the swelling chorus for women’s suffrage, the upcoming election included Amendment 6 granting a female franchise. The Evening Breeze was positive: “There is little doubt but the proposed amendment … will be carried.” Of course, the rhetoric compared the current status of women to slaves, “subject to the will of the master,” denied all sorts of prerogatives available to men, and some, mere “beasts of burden.” The writer was most likely unaware of the women’s achievements mentioned last month, nor that the State Constitution did not prohibit them from entering professional careers.

As a state, California replicated much of the nation by cheering progress, chastising dissenters, and climbing the summit at whose top awaited the reward of national law and not simply state directives. Yet, the battle needed to be fought state by state.

Decades of advocacy, failures, and successes large and small emboldened the cause. “Failure is impossible” was the mission statement. Many Californians dearly wanted to join the elite group of states led by Wyoming in 1890, then Colorado three years later in extending the franchise to resident women. All it took was to convince a majority of voter—all male—to agree with them.

The story continues.

In the small county and even smaller county seat with the same name, San Luis Obispo suffragists were eager to have their voices added to the grander scale marches by suffragettes in their blue, gold, and green regalia. Distractors were expected as the Sacramento Bee reported in 1895. It seems those opposed to the idea used female association with bloomers and pantaloons to ridicule the advocates as “pantaloonatics.”

Undeterred by any name-calling, locally, the Political Equality Club of about 20 ladies (and three men) “became a very lively aggressive organization” in May 1896 preparing for the pivotal November state election. Composed of many leading members of the community, any opponents were characterized by the press as “Salurians” or rock brains. The editor praised the gathering which showed “plainly that the women of this city—the wives and mothers—know what they want, and propose to obtain it if open argument and honest effort can obtain it.”

Included among the leaders were Francis Margaret Milne, soon to be the city librarian (see April 2019 issue) and Miss Kate Cox who preferred being characterized as a “capitalist.” She will become the oldest woman in the county to register to vote once approval was secured in the state. The ladies were in a “feverish state of excitement” and men were advised to remain silent.

Adding their voices to the swelling chorus for women’s suffrage, the upcoming election included Amendment 6 granting a female franchise. The Evening Breeze was positive: “There is little doubt but the proposed amendment … will be carried.” Of course, the rhetoric compared the current status of women to slaves, “subject to the will of the master,” denied all sorts of prerogatives available to men, and some, mere “beasts of burden.” The writer was most likely unaware of the women’s achievements mentioned last month, nor that the State Constitution did not prohibit them from entering professional careers.

Contemporary luminaries such as Laura de Force Gordon and Clara Shortridge Foltz were among a bevy of notables in the state and nation.

An enterprising reporter asked some men about their views. “As long as they pay taxes,” opined one. A loftier prospect envisioned the female voter as “a purifying element to politics everywhere.” Fearful of offending anyone, a large number of opinions “did not desire to be quoted.” In any case, the voting new women promised to change the nation. Speakers poured into the small county of 16,000 residents to encourage the cause. One even promised, “The vulture of prejudice will be shot out of the heaven of politics…” Indeed.

The Political Equality Club’s “indefatigable labors” secured a presentation by “the grand Christian lady,” Susan B. Anthony, on October 12 on her lecture tour. By then, the 76-year-old Quaker had battled for the woman’s right to vote across America along with decades devoted to the abolishment of slavery. Defying the law, she was arrested for voting. It was for that “crime” that President Trump issued a Presidential pardon celebrating the centennial of the 19th Amendment. While Anthony did not live to witness the Constitutional Amendment, her image is on the now rarely used one dollar coin.

It was another friend and pioneer suffragist, Ellen Clark Sargent’s husband, Senator Aaron Sargent, a Republican representing California, who introduced a resolution in Congress in 1878 as a precursor to the 19th amendment. In a rare occasion, the Senate allowed suffragists to testify.

Anthony’s presence was a gala honor. Singing America, “with much fervor,” a capacity audience with many turned away, Anthony spoke for about an hour. While “well-advanced in years,” her enthusiasm and message had an often-cheering audience, reported the press. She warned if the upcoming vote was not favorable, “the fight would be waged again.” Promising peace in the family, “the men might just as well vote ‘yes’ this time.”

Ignoring the warning, Amendment 6 was defeated in the November 7 general election. It would be an oversimplification to determine it was a battle between the sexes. Nearly 45% voted in favor with 55% opposed and San Luis Obispo County’s 3,200 voters were in favor by approximately 60 to 40 percent. The major opposition came from the larger cities, especially San Francisco.

Anthony’s presence was a gala honor. Singing America, “with much fervor,” a capacity audience with many turned away, Anthony spoke for about an hour. While “well-advanced in years,” her enthusiasm and message had an often-cheering audience, reported the press. She warned if the upcoming vote was not favorable, “the fight would be waged again.” Promising peace in the family, “the men might just as well vote ‘yes’ this time.”

Ignoring the warning, Amendment 6 was defeated in the November 7 general election. It would be an oversimplification to determine it was a battle between the sexes. Nearly 45% voted in favor with 55% opposed and San Luis Obispo County’s 3,200 voters were in favor by approximately 60 to 40 percent. The major opposition came from the larger cities, especially San Francisco.

A corollary issue was the growing influence of anti-alcohol groups including the Women’s Christian Temperance Movement with many members also suffragettes. If women could vote, there would be further erosion on the availability of alcohol. The concern proved correct a quarter-century later. In one of those delightful historical alignments, 1920 not only celebrated the 19th Amendment but also the implementation of the 18th Amendment. The birth of Prohibition, the sorted years of avoidance, enforcement, and the advent of organized crime led to its repeal in 1933 … the only repeal of a Constitutional Amendment. It seems the virtue of voting did not replicate itself in the imposition of the virtue of temperance on others.

Persistence. Again, the crusade continued and California was successful some fifteen years later on October 10, 1911, joining the other five states including women voters. Of some half-million votes cast, the slim majority was 3,587. It doubled the number of women eligible to vote in America. While still opposed by San Francisco voters, the bay area city became the largest concentration of female voters in the nation.

Among the followers was Queenie Warden who was the first woman to run for mayor of San Luis Obispo related in these pages in January 2015. Her narrow defeat ended with her promising “I will be back” spoken not so much of her ambitions but women officials in general. While she didn’t seek political office again, in 1962, Margaret McNeil became the first woman to serve on the City Council. From then to now, the political woman’s profile has changed dramatically. What differences it has made is worthy of further discussion.

Persistence. Again, the crusade continued and California was successful some fifteen years later on October 10, 1911, joining the other five states including women voters. Of some half-million votes cast, the slim majority was 3,587. It doubled the number of women eligible to vote in America. While still opposed by San Francisco voters, the bay area city became the largest concentration of female voters in the nation.

Among the followers was Queenie Warden who was the first woman to run for mayor of San Luis Obispo related in these pages in January 2015. Her narrow defeat ended with her promising “I will be back” spoken not so much of her ambitions but women officials in general. While she didn’t seek political office again, in 1962, Margaret McNeil became the first woman to serve on the City Council. From then to now, the political woman’s profile has changed dramatically. What differences it has made is worthy of further discussion.