WHATEVER THEIR JOURNEY TO THE SMALL COUNTY IN the middle of California, each of the pioneer librarians (1919-1958) left a legacy of professional determination to enhance and enrich the cultural beacon of literacy. While each day was met by the exigencies of the time, the goal was more than surviving the moment but envisioning a future where primarily books would freely reach willing hands. Certainly, a daunting task given the realities of human strength and bureaucratic budgets, each had a personal life—often in itself a saga of sadness as well as joy—that paralleled their days.

In both their personal and professional pursuits, each handed the baton of literacy on to a successor until today. Each deserves to be celebrated and remembered by those who reap the benefits of their efforts.

The story continues.

San Luis Obispo County lost a longtime friend when Marion Fechet Kilburn died in August 1948. Her successor stayed for a much shorter term.

While born in 1892 in Anthon, Iowa, Lila Grace Dobell received advanced education in Oregon and became a well-seasoned veteran of the library world having served in the library of her alma mater, Oregon Agricultural College (today’s Oregon State University), followed by librarian for the Trinity County (California) system beginning in 1921. In November of the following year, she married local garage owner Henry Alvin Adams from Weaverville and began a family the following June with the birth of their son, Harold.

By 1940, however, Lila is listed in the Federal Census as divorced and from then on, her life is a series of professional moves mostly following her son as he eventually forged his own family and career.

In 1941, her son now an adult, Lila assumed librarianship for nearby Glenn County for three years and then to the Paso Robles Library until her appointment locally on July 1, 1948.

For January 1949, the annual statistics reflected 64 distribution points including 21 community branches for nearly ten thousand borrowers with a circulation over 137 thousand volumes. The report included service to rural schools although the responsibility ended the previous July. There was little change over the next 39 months when she submitted her resignation in 1951.

Stating she was moving to the east coast, undoubtedly, an important consideration was the anticipated birth of her granddaughter in Pennsylvania. Over the next five years, Lila will be noted as serving in five different libraries in three different states. Most often, each assignment was close to her son and family.

Certainly, Lila cannot be faulted for placing her family before her profession as she disappears from records in 1956 when she files a claim for Social Security benefits at age 64. Another notation of February 2, 1979, may be a death date.

Locally, rather than seek a replacement, the Board of Supervisors appointed a long-serving staffer as an interim director.

Bertha Franklin

Longevity of service is not unusual in the library world. Undoubtedly, Abelina Freeborn set the record with 48 years as guardian of the collection for the Simmler Branch, but she was not alone in the 40-plus years category.

Bertha Franklin, however, set a record having served in the administration from 1920 when she joined the first county librarian, Margaret Dold, to serve a population of about twenty-two thousand. With no training, she started employment with the City Library before transferring to the County. She summarized her rationale: “better salary-better future-better hours.”

Working her way from assistant to interim director started as a journey of a widow with two children when her husband, Fred Harpster, unexpectedly died in 1918 to spanning forty years of service when she retired in 1958.

Bertha proved to be a unifying presence among the six pioneer librarians as an active participant as headquarters moved six times, branches were begun and “suppressed,” and experienced untold numbers of visits to bring multi-thousands of books and supplies to varying branches and schools. Undoubtedly, she had near endless tales gathered from the public and staff.

On a personal note, between motherhood and employment, she remarried Paul Franklin in 1927.

Helping to manage the growing countywide enterprise, Franklin’s last boss was the most notable appointment in her administrative life with leadership entrusted to the first male county librarian.

Walter Austin Sharafanowich

“A new Head Librarian is always expected to make some changes— and we didn’t want to upset the tradition.” So began Walter’s first official greeting to library personnel. Published over many years, the monthly newsletter fostered a community of like-minded public servants rather than the usual bureaucratic “flow chart” of duties and responsibilities.

If a color were assigned to a personality, WAS—as he most often referred to himself—could easily be depicted in bright hues. He saw himself and was seen by others as more than the chief guardian of books. A linguist (Russian, French, and German), thespian, interior decorator, and gourmet, his interests underscored a man of many talents beyond his livelihood.

The first county librarian born in the 20th century (1920) in New York City of Russian immigrants, by 25, he already served as an interpreter in Slavic languages with the Army in Europe. Over the next several years, he returned to the east coast for a degree from the University of North Carolina (1948) and then back to the west coast for a Master of Arts degree from Stanford University the next year and in 1951, a Bachelor of Library Science from the University of California (Berkeley).

His first professional assignment began locally on September 15, 1952 and he lost no time being sure he communicated the importance of the library through both the airwaves and the press. In a county of about 52,000 residents spread over a mostly agricultural community, use of radio broadcasting was one way to encourage patronage. Another was newspaper articles entitled “From a Bookie Joint” that profiled books, libraries and personnel. At the time there were 22 branches scattered throughout the county from San Miguel to Oceano.

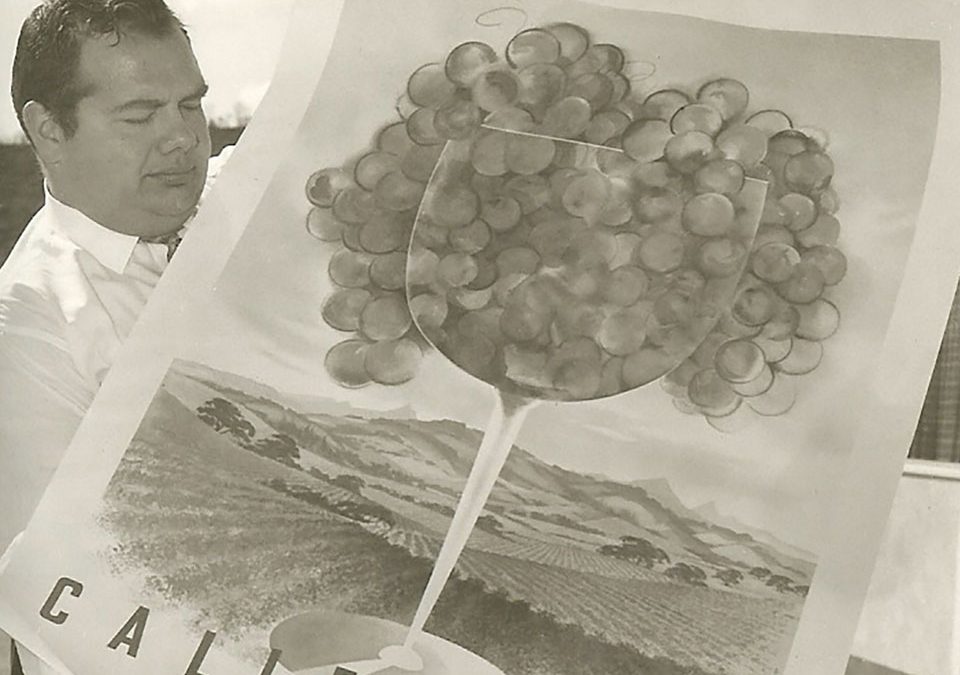

Not so public were his candid notes from various meetings and encounters with staff and community. He was especially riled when the Atascadero Women’s Christian Temperance Union complained about a poster celebrating the county’s wine industry. He removed the sign but considered their “niggardly censorship” as being “neither Christian nor Temperate.”

Nor was he content with simply being the chief administrator for the county system. He soon was a regular participant in various Little Theatre productions, even winning an “Oscar” for his performance in the comedy Little Angels.

His enthusiasm and exuberant personality seemingly outgrew the small county and its small library system. Walter resigned effective September 1958 to accept a position in the Alameda Free Public Library and was characterized by the press as a “librarian-gourmet-thespian.” The post lasted for six years when he entered the education world in the Brentwood (California) high school as their librarian. It was an especially challenging job as the library was mostly destroyed by a fire the previous year. It proved his last assignment until he retired in 1983.

With WAS, the county library system began a slow transition to a more modern institution. Collections would no longer be found in living rooms and post office locations would be phased out. His successor, Lois Crumb King, left an invaluable daily log of meetings, issues and solution until she retired in 1970.

Her successor, Dale Perkins, the longest serving county librarian, oversaw a service crippled by devastating funding issues, yet rebounding with the most ambitious building program in the library’s history.

Thus, until the present day, both individually and collectively, the pioneer librarians reflect the journey of many in the quest for greater literacy and liberation primarily through words in books. That the future will depend less on books and more on technology does not negate the essential function of a library nor the often-heroic efforts of its pioneers.