In any community retrospect, there are influential figures from the past who left a notable imprint upon the life of future generations only to eventually recede into the mists of time and memory. Some are so important, so remembered, a grateful heritage may erect statues in their honor, name streets, public spaces— even newborns— after them.

Yet, those so honored may never have lived even close to the grateful municipality … indeed, may never have even heard the name. Certainly, the Spanish explorer, Gaspar de Portola, merely rode across the western fringe of the present county in 1769 … yet has a street name. It is doubtful Andrew Carnegie even knew he donated $10,000 to build the first library in the county remembered today as the History Center. There is one recorded notation when he rode the train across the county … only to be stopped by a collapsed tunnel through the Cuesta Pass!

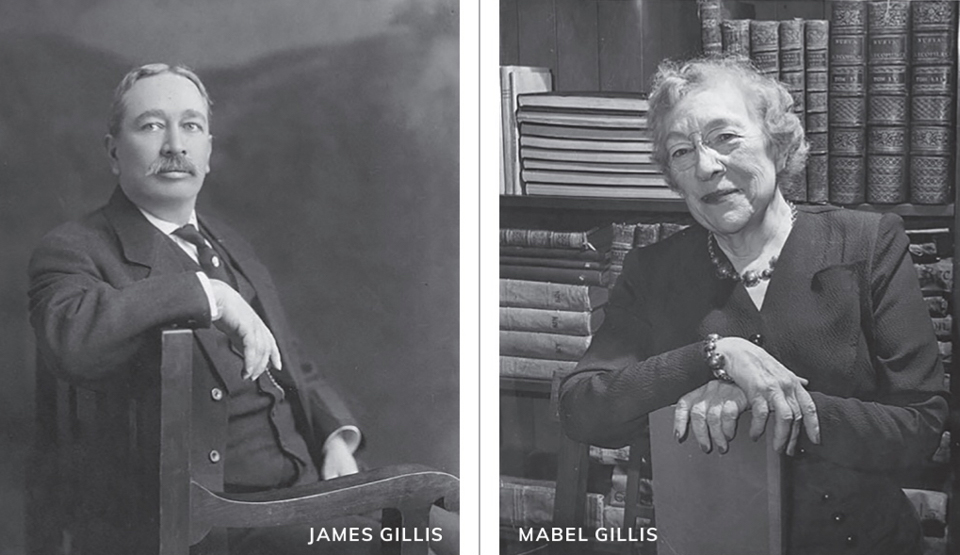

So, why should James Louis Gillis even deserve a footnote in local community history? In fact, why should he be remembered throughout virtually every community in the state?

The succinct answer: He invented the library.

Here’s the story.

It is a bit of an exaggeration to claim he “invented” the library. More accurately, shortly after the turn of the last century, he worked diligently in a revolutionary proposal to assure some sort of collection was available— at no charge —to most anyone in the state who wanted to read a book or magazine or newspaper. True, there had been some community efforts already to establish a library. The first in the county began in San Luis Obispo in 1894 but was accessible only to city residents for a fee.

Desire and wishes needed a political foundation if collections were to be available to all. The perfect man at the perfect location, Gillis’ vision coupled with an indomitable determination assured the laws of the state supported the cultural icon.

He didn’t apply for the position as the State Librarian. Born in Iowa in 1857, a school drop-out at 14, then twenty years working his way up to prominent positions for the all-powerful railroad, chief clerk for the Assembly Ways and Means Committee, “active and well-known in Republican party circles” and deputy State Librarian preceded his appointment in 1899. For him, the job ceased being a political reward received with “little desire to serve the people of the state.”

Gillis had a simple plan: if education placed school houses close to students, then libraries needed to be close to readers. Indeed, education would be extended beyond “a few youthful years” as a lifetime pursuit.

The new State Librarian implemented a variety of efforts to promote literacy. Beginning in 1903, five community members could request a traveling library where 50 books were sent free of charge to anywhere willing to host a location and become their guardian. Ten were in this county. If groups were formed to encourage the systematic study, $1.50 would assure 25 books for use. Need help organizing or improving a community library? State employees were available for consultation. Ten to twenty-five books for the blind were sent to any public library for the benefit of impaired patrons at no charge. Joining her father in 1904, Gillis’ 27-year-old daughter, Mabel, headed the department and would serve as the first woman to head the State Library (1930-1951).

Yet, more was needed. An audacious plan, Gillis envisioned a statewide library system. Both the laws and the resources of the government needed to be tailored to promote the daring proposal. He dreams were not simply another state mandate but “will make an epoch in the history of the library development.”

The grandiose plan required strategic implementation. In rapid order, in 1909 legislation was introduced to assure the vision could become a reality. County boards of supervisors were authorized to establish a central library and branches; by requiring a “certified librarian,” he established training programs as there were no courses offered in the state university. Boldly, Gillis recommended the state budget for school books be part of a unified library system where both the school and community stations operated with increased efficiency. Revenue to schools for books could be combined with the county librarian purchasing the required texts and other educational supplies. Any library was considered a partner with the state library and its expanding collections.

As expected, not everyone embraced the plan with some claiming it was a political power grab to rob counties of local budget control. Some believed books were a personal expense; not a taxation item. Depending on increased communications, in 1906, Gillis instituted Library News Notes. Monthly, then quarterly reports from throughout the state listed every library, revenues, statistics and local library news. Fortunately, a complete set of this invaluable resource has been preserved in the County Library Archives.

Printed communication was not sufficient. In a remarkable choice, Gillis asked Harriett G. Eddy to become the first County Free Library Organizer. For a decade, the intrepid Eddy traveled throughout the state campaigning for counties to establish libraries as related in these pages (December 2017 and January 2018). Her efforts in this county eventually resulted in the establishment of a county library and the hiring of Margaret Dold as the first Librarian beginning on July 1, 1919. The county was one of the last in the state to institute the service. The remarkable efforts to bring literacy into every community is recounted in this writer’s “A History of the San Luis Obispo County Library.”

Dold was one of dozens of “Gillis Girls” who received training and recommendations through the central office in Sacramento. At the time, the choices for a woman to seek a career outside the home were limited with librarianship an early alternative.

Service from Sacramento vastly surpassed the ability of its home. Gillis had the answer: build a new State Library. Again, depending on the Legislature to allocate the funds, Gillis was a key promoter for the elegantly striking building eventually to open in 1928. Indeed, it was on the way to yet another meeting addressing the future library home that he suffered a heart attack and died on July 27, 1917.

Lauded as a man who “lived a life of right deed and right thought,” his deputy and successor, Milton J. Ferguson, provided a fitting eulogy for his fallen leader:

“There was something magical in the way he shook your hand: a firm grip which gave you a message of hopefulness, of buoyancy, of determination. He was never too weary to come to the aid of a right cause … To his last hour he was in the front rank of the charge, his courage high, his aim true. For the past he had no regrets; for the future no fear.”

With unexpected vigor for a political appointee, Gillis had provided a unique basis for the libraries in California to become the peoples’ university. Anyone could enter the doors of however humble the structure and find standing at attention books capable of entertainment or instruction, a paper vehicle capable of transporting the curious into worlds afar, or simply a short poem that somehow proved more curative than all medicine.

For his enthusiasm and passion for an enriched future, better equipped through the library’s offerings, James L. Gillis, indeed needs to be honored throughout the state.

Contact: jacarotenuti@gmail.com